The global energy landscape is witnessing a profound shift, with a once-beleaguered industry now experiencing an unexpected resurgence. Nuclear power, long overshadowed by concerns over safety, cost overruns, and waste disposal, is re-emerging as a pivotal player in the quest for clean, reliable energy. This renewed interest is largely fueled by the promise of small modular reactors (SMRs), innovative designs that proponents believe can overcome the hurdles that plagued traditional, colossal nuclear power plants. A testament to this burgeoning optimism, nuclear startups attracted an astounding $1.1 billion in investor capital in the final weeks of 2025 alone, signaling a fervent belief in the transformative potential of these compact energy solutions.

A Resurgent Industry’s Financial Backing

This significant influx of investment underscores a broader market confidence in a technology poised to address pressing global energy demands. For decades, the construction of new nuclear power plants, particularly in Western nations, has been a rarity, hampered by prohibitive costs, lengthy construction timelines, and complex regulatory frameworks. However, the escalating urgency of climate change, coupled with the need for stable, carbon-free baseload power to complement intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind, has cast nuclear energy in a new, more favorable light. Investors, including prominent venture capital firms and major tech players, are now actively betting on a future where smaller, factory-built reactors can deliver on the long-held promise of nuclear power without the historical baggage.

The Promise of Smaller Reactors

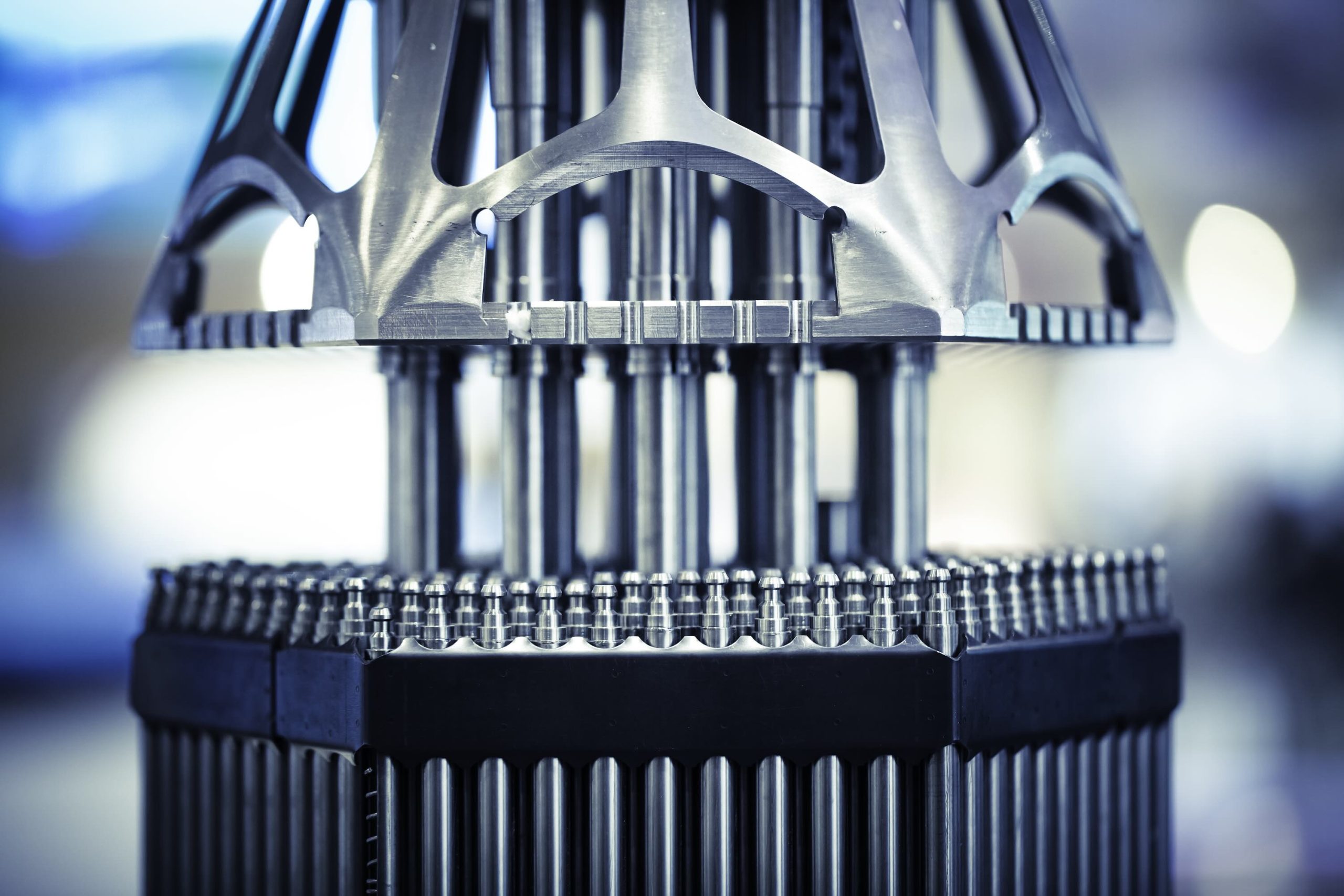

Traditional nuclear power facilities are monumental feats of engineering, requiring immense on-site construction and staggering financial commitments. A prime contemporary example in the United States, the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant’s Units 3 and 4 in Georgia, illustrates this scale and its inherent challenges. These reactors, each designed to produce over a gigawatt of electricity, involved the deployment of tens of thousands of tons of concrete and towering fuel assemblies. While powerful, their construction was plagued by severe delays, ultimately arriving eight years behind schedule and exceeding their budget by more than $20 billion. Such experiences have solidified the perception that large-scale nuclear projects are financially risky and logistically daunting.

In stark contrast, the new generation of nuclear startups champions the concept of miniaturization and modularity. By significantly shrinking the reactor core and its associated components, these companies aim to sidestep the twin problems of cost escalation and protracted schedules. The vision is to manufacture reactor components, or even entire reactor units, in controlled factory environments using standardized designs and advanced production techniques. This approach, they contend, will enable economies of scale and learning curve benefits, where each successive unit becomes cheaper and quicker to produce as manufacturing processes are refined. Should a utility require more power, the solution would be to simply add more modular units, rather than embarking on another multi-decade, multi-billion-dollar megaproject. This "build many, build better" philosophy forms the bedrock of the SMR movement’s economic argument.

Manufacturing: The Unseen Crucible

While the theoretical advantages of SMRs are compelling, translating this vision into widespread reality presents formidable manufacturing challenges. The promise of cost reduction through mass production, often referred to as "learning by doing" or experience curve effects, is a well-established economic principle. However, the magnitude of this benefit in the highly specialized and regulated nuclear sector remains an active area of research and debate among experts. The assumption that these benefits will materialize significantly and rapidly is a critical cornerstone of investor optimism, yet it is far from guaranteed.

The complexities of advanced manufacturing are not to be underestimated, even for seemingly simpler products. Milo Werner, a general partner at DCVC and co-founder of the NextGen Industry Group, offers a sobering perspective drawn from her extensive experience in industrial production, including a tenure leading new product introduction at Tesla. She highlights Tesla’s arduous journey to profitably mass-produce the Model 3 electric vehicle. Even with the inherent advantages of operating within the established automotive industry, a sector where the U.S. retains considerable manufacturing expertise, Tesla faced immense hurdles. The nuclear industry, striving to establish an entirely new manufacturing paradigm, lacks such a foundational advantage.

Erosion of Industrial Expertise

Werner points to a critical systemic deficiency: the erosion of the domestic manufacturing supply chain and human capital. "I have a number of friends who work in supply chain for nuclear, and they can rattle off like five to ten materials that we just don’t make in the United States," Werner noted, emphasizing that many essential specialized components and raw materials must be procured from overseas. This reliance on foreign sources is not merely an inconvenience; it represents a deeper problem: the U.S. has "forgotten how to make them." Decades of offshoring manufacturing across various sectors have led to a significant loss of critical industrial capabilities and the skilled workforce required to operate them.

This "muscle memory" deficit extends beyond specific materials to the broader human capital required for large-scale industrial endeavors. "We haven’t really built any industrial facilities in 40 years in the United States," Werner explained, likening the situation to an athlete attempting a marathon after years of inactivity. The nation lacks a sufficient cadre of experienced professionals across the entire manufacturing spectrum – from skilled machine operators and factory floor supervisors to seasoned project managers, supply chain specialists, and even executive leadership with a deep understanding of complex industrial production. While capital is currently abundant in the nuclear startup ecosystem, as Werner observes, "They’re awash in capital right now," money alone cannot instantly conjure the necessary expertise.

Rebuilding the Manufacturing Muscle

The challenges facing nuclear SMR startups are multifaceted, encompassing not only the technical complexities of reactor design but also the intricate art of industrial production within a highly regulated environment. The stringent safety and quality requirements inherent in nuclear technology amplify every manufacturing hurdle. Unlike consumer electronics or even automobiles, errors in nuclear component fabrication carry exceptionally severe consequences, demanding unparalleled precision, robust quality control, and rigorous testing protocols at every stage.

Despite these significant obstacles, there are encouraging signs of adaptation and innovation within the startup landscape. Werner observes that many nascent companies, both in nuclear and other advanced manufacturing sectors, are wisely choosing to build early versions of their products in close proximity to their technical teams. This strategy facilitates a rapid feedback loop between design and production, allowing for iterative improvements and problem-solving. This localized approach is effectively "pulling manufacturing in closer to the United States because it allows them to have that cycle of improvement," she says.

Furthermore, investors are increasingly keen on startups that embrace modularity not just in their product design but also in their manufacturing strategy. "Really leaning into modularity is very important for investors," Werner advises. This enables companies to begin producing small volumes early on, generating invaluable data on the manufacturing process itself. This data-driven approach, if it demonstrates continuous improvement over time, can provide crucial reassurance to investors and de-risk future scaling efforts.

The Long Road Ahead

The journey from innovative design to widespread, cost-effective deployment for SMRs is likely to be a protracted one. While the concept of a learning curve suggests eventual cost reductions, the timeframe for realizing substantial benefits from mass manufacturing can be extensive. Werner cautions that "Often it takes years, like a decade, to get there." This long horizon necessitates sustained investment, unwavering political will, and a dedicated effort to rebuild the nation’s industrial capabilities and human capital.

The renewed enthusiasm for nuclear power, particularly through the lens of SMRs, represents a significant pivot in the global energy conversation. It offers a compelling vision of a carbon-free future powered by reliable, scalable energy. However, for this vision to materialize, the industry must not only perfect its reactor designs but also meticulously reconstruct the manufacturing infrastructure and cultivate the human expertise that has atrophied over decades. The success of this nuclear renaissance hinges not just on scientific ingenuity, but on the painstaking, often unglamorous, work of industrial production and the re-establishment of a robust domestic manufacturing ecosystem. The billions flowing into these startups are a powerful vote of confidence, but the true test will be the industry’s ability to forge a new manufacturing reality from the ground up.