A powerful coalition of Japanese content creators and publishers, spearheaded by the Content Overseas Distribution Association (CODA), has formally requested that OpenAI cease the unauthorized use of their copyrighted works for training its advanced artificial intelligence models. This demand, delivered in a direct communication to the AI development powerhouse, highlights a growing international friction point at the intersection of technological innovation and intellectual property rights, particularly as generative AI tools like OpenAI’s DALL-E, ChatGPT’s image generator, and the groundbreaking Sora video model become increasingly sophisticated and accessible.

The Core Dispute: Unauthorized Training Data

At the heart of the controversy lies the fundamental mechanism of generative AI. These systems, designed to create new content—be it text, images, or video—learn by analyzing vast datasets, often comprising billions of examples sourced from the internet. This training process allows the AI to identify patterns, styles, and elements, which it then synthesizes to produce novel outputs. For many AI developers, including OpenAI, the assumption has often been that ingesting publicly available data for training falls under principles akin to "fair use" or data mining exceptions in various jurisdictions, allowing for the rapid advancement of their models without explicit prior permission from every copyright holder.

However, content creators globally are increasingly challenging this stance. They argue that the wholesale ingestion of their works, without licensing or compensation, constitutes a direct infringement of their intellectual property. The resulting AI-generated content, while not always a direct copy, often mimics the distinctive styles and elements of original works, potentially devaluing the human-created originals and disrupting established creative industries. CODA, representing a significant portion of Japan’s vibrant entertainment sector, including renowned animation studios and publishing houses, articulates this concern vividly.

Studio Ghibli: A Symbol of Artistic Integrity

Among the most prominent entities represented by CODA is Studio Ghibli, the celebrated animation studio behind globally acclaimed films such as "Spirited Away," "Princess Mononoke," and "My Neighbor Totoro." Ghibli’s distinctive artistic style, characterized by its hand-drawn aesthetics, evocative storytelling, and profound emotional depth, has cultivated a devoted international following. The studio’s work is not merely entertainment; it represents a unique cultural and artistic legacy.

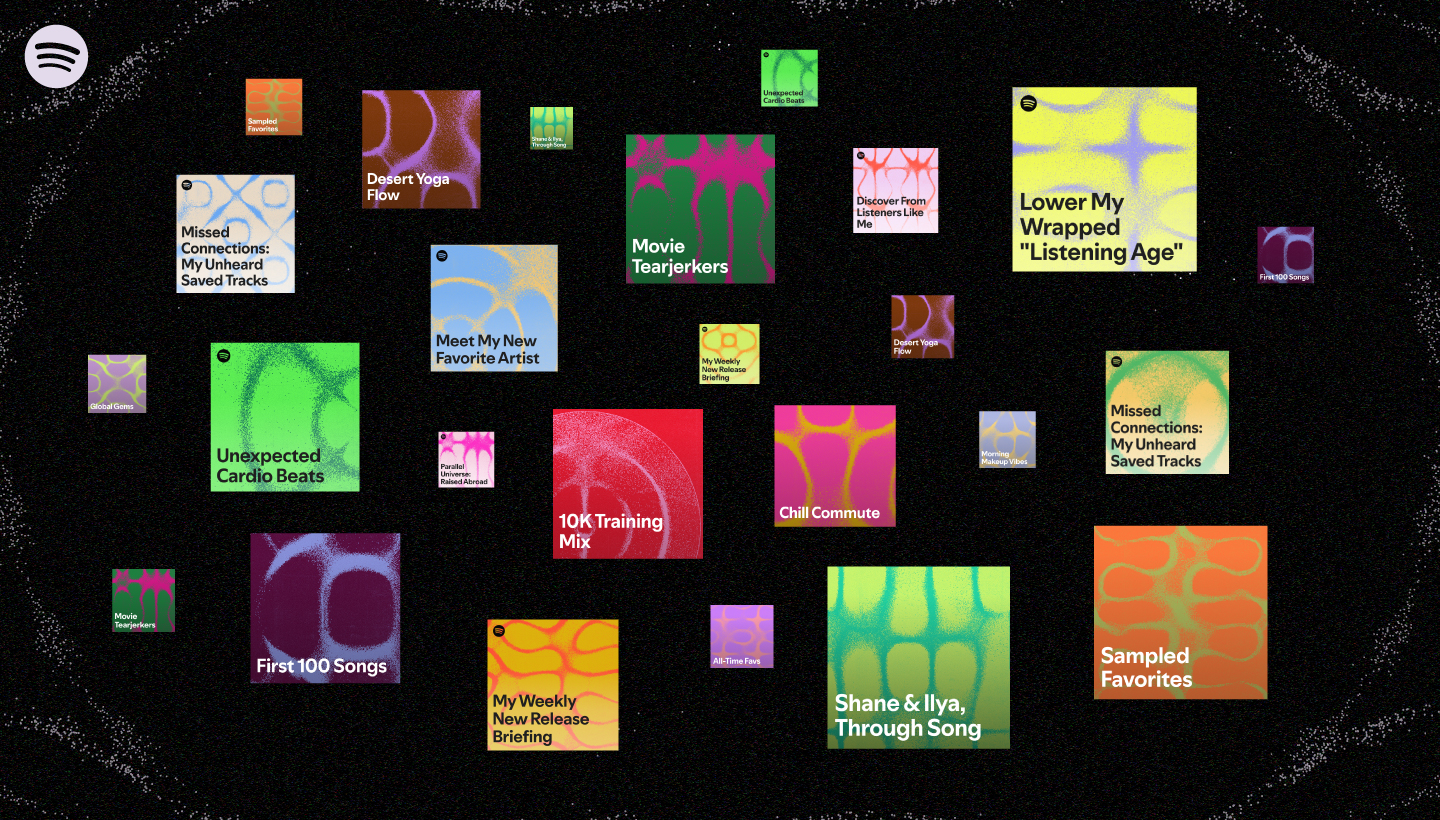

The impact of generative AI on Studio Ghibli’s brand became particularly evident with the release of ChatGPT’s native image generation capabilities. Almost immediately, a widespread trend emerged where users leveraged the AI to create images in the "Ghibli style," ranging from stylized portraits to fantastical landscapes. This phenomenon, often dubbed "Ghiblified" content, quickly went viral across social media platforms. Even OpenAI CEO Sam Altman briefly adopted a "Ghiblified" version of his own profile picture on X (formerly Twitter), underscoring the AI’s ability to replicate the studio’s iconic visual language. While these creations demonstrated the AI’s capacity for mimicry, they also ignited a debate about the ethical implications of such appropriation, raising questions about originality, authorship, and the potential erosion of unique artistic identities.

The concern has intensified with the advent of OpenAI’s Sora, a text-to-video generation model capable of producing highly realistic and imaginative short video clips. The potential for Sora to generate complex animated sequences in specific artistic styles, including those of renowned studios like Ghibli, without direct human input or compensation, presents an even more significant challenge to traditional animation pipelines and copyright protection.

The Broader Landscape of Generative AI

The friction between content creators and AI developers is not an isolated incident involving CODA and OpenAI. It is part of a much larger, ongoing global discourse spurred by the rapid evolution of generative AI. The AI industry, driven by a philosophy of accelerated development and iterative improvement, has often adopted an "ask for forgiveness, not permission" approach when it comes to data acquisition. This strategy allows companies to quickly build and deploy powerful models, but it simultaneously pushes the boundaries of existing legal frameworks and sparks widespread discontent among artists, writers, musicians, and other creators whose works form the foundational data for these systems.

Numerous high-profile lawsuits and public outcries have emerged in recent years. Major news organizations, including The New York Times, have initiated legal action against OpenAI, alleging copyright infringement for using their articles to train AI models. Similarly, visual artists and photographers have sued companies like Stability AI and Midjourney, claiming their works were scraped from the internet and used without consent to train image generators. Stock photo giant Getty Images also filed a lawsuit against Stability AI, asserting that the AI model generated images containing modified versions of their watermarked content, indicating direct copying. These cases collectively underscore the urgent need for clarity and updated legal interpretations in the digital age.

Legal Labyrinth: US vs. International Copyright

The legal landscape governing AI training on copyrighted material remains largely uncharted and complex, particularly when considering international jurisdictions. In the United States, the concept of "fair use" is a cornerstone of copyright law, allowing for the limited use of copyrighted material without permission for purposes such as commentary, criticism, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Courts typically weigh four factors: the purpose and character of the use (including whether it is transformative), the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

AI developers often argue that training an AI model is "transformative" because the AI doesn’t reproduce the original work directly but rather learns from it to create new, distinct outputs. They also contend that the sheer scale of data processing, often involving billions of data points, makes individual licensing impractical. However, creators argue that the economic impact is undeniable, as AI-generated content can directly compete with and devalue their original creations. The US Copyright Act itself, last substantially updated in 1976, predates the internet, let alone the era of generative AI, making its application to these novel technologies a subject of intense judicial and legislative debate.

A Precedent in Flux: The Anthropic Case

Adding to the legal ambiguity is a recent ruling involving Anthropic, another prominent AI company. A US federal judge, William Alsup, found that Anthropic did not violate copyright law merely by training its AI on copyrighted books. This decision, if upheld, could set a significant precedent by suggesting that the act of training itself might not constitute infringement under certain interpretations of US law. However, critically, Anthropic was fined for pirating the books it used for training, highlighting that while the act of "learning" might be permissible, the unlawful acquisition of the training data remains a clear violation. This distinction is crucial: it suggests that the legality might hinge less on the process of AI training and more on the source and acquisition method of the data. The legal nuances of this case continue to be analyzed, offering a partial, yet incomplete, glimpse into future court decisions.

Japan’s Distinct Legal Stance

CODA’s communication to OpenAI specifically emphasizes that the situation may be viewed very differently under Japanese copyright law. Unlike the more flexible "fair use" doctrine prevalent in the US, Japan’s copyright system generally requires prior permission for the use of copyrighted works. There is no broad "data mining" exception that would automatically exempt AI training from needing consent, nor is there a system allowing parties to avoid liability for infringement through subsequent objections or negotiations.

CODA explicitly states, "In cases, as with Sora 2, where specific copyrighted works are reproduced or similarly generated as outputs, CODA considers that the act of replication during the machine learning process may constitute copyright infringement." This suggests that even the internal replication of data within an AI model’s training process, or the generation of outputs that too closely resemble original works, could be deemed illegal under Japanese statutes. This divergence in legal frameworks between major economic powers like the US and Japan underscores the global challenge of regulating AI and intellectual property. It also raises complex questions about how multinational AI companies operating across borders can navigate disparate legal expectations.

Miyazaki’s Unflinching Stance on AI

While Studio Ghibli itself has not issued an official statement regarding the current dispute, the philosophical stance of its co-founder and legendary director, Hayao Miyazaki, offers powerful insight into the studio’s probable perspective. In a widely circulated video from 2016, Miyazaki was shown a demonstration of AI-generated 3D animation. His reaction was unequivocal and deeply critical. He described himself as "utterly disgusted" by the technology.

"I can’t watch this stuff and find it interesting," Miyazaki stated at the time, his disapproval palpable. He went on to articulate a profound ethical objection, declaring, "I feel strongly that this is an insult to life itself." His comments highlight a deeply ingrained belief in the unique value of human creativity, effort, and the soul that artists imbue into their work—a value he sees as fundamentally incompatible with the mechanistic generation of art by machines. This perspective, shared by many traditional artists, frames the current debate not just as a legal squabble over property, but as a cultural and philosophical confrontation over the very definition and essence of art.

The Future of Creativity and AI: Navigating the Ethical Divide

The dispute between CODA and OpenAI is a microcosm of a larger societal reckoning. As AI capabilities continue their exponential growth, the tension between fostering innovation and protecting human creators will only intensify. The outcome of these legal and ethical challenges will likely shape the future trajectory of both the AI industry and creative sectors worldwide.

Potential resolutions could involve new legislative frameworks specifically designed for the AI era, international treaties to harmonize copyright protections across borders, or novel licensing models that allow AI companies to legally access and compensate creators for their data. Some AI companies are beginning to explore licensed datasets, partnering with content providers, but this approach is still nascent and does not cover the vast amounts of unlicensed data already ingested. The demand from CODA and the unequivocal stance of figures like Hayao Miyazaki serve as a stark reminder that the pursuit of technological advancement cannot ethically or sustainably proceed without a clear, equitable framework for respecting and rewarding human ingenuity. The global community is watching closely as courts and policymakers grapple with these profound questions, aiming to strike a balance that allows both creativity and innovation to flourish.