SpaceX, the aerospace manufacturer and space transportation services company founded by Elon Musk, has submitted a groundbreaking application to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), seeking authorization to deploy an unprecedented constellation of up to one million solar-powered satellites designed to function as orbital data centers for artificial intelligence. This audacious proposal represents a significant escalation in the company’s vision for space utilization, extending beyond global internet provision to establish a new frontier for high-performance computing.

The company’s filing paints a grand narrative, positioning these proposed satellites as not merely the most efficient solution for the escalating demand for AI computing power, but also as a crucial stepping stone towards humanity achieving a "Kardashev II-level civilization." This concept, derived from Russian astrophysicist Nikolai Kardashev’s scale of technological advancement, describes a civilization capable of harnessing the entire energy output of its host star. SpaceX explicitly links this project to the broader ambition of "ensuring humanity’s multi-planetary future amongst the stars," a recurring theme in Musk’s long-term objectives for the company.

The Vision for Orbital AI

At its core, SpaceX’s proposal addresses a critical bottleneck in the current technological landscape: the insatiable demand for computational power driven by the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence. Modern AI models, particularly large language models and complex neural networks, require immense processing capabilities, which are currently housed in terrestrial data centers. These facilities consume vast amounts of land, energy, and cooling resources, leading to significant environmental footprints and geographical limitations.

Moving data centers into Earth orbit, particularly those powered by solar energy, theoretically offers several advantages. Firstly, access to uninterrupted solar power in space could provide a more consistent and potentially greener energy source compared to ground-based grids, which often rely on fossil fuels. Secondly, the vacuum of space offers a natural cooling environment, potentially reducing the energy overhead associated with maintaining optimal operating temperatures for high-density computing hardware. Lastly, by placing AI processing capabilities closer to the source of data, such as other satellites or future space-based platforms, latency could be reduced, enabling more rapid and efficient data analysis for applications ranging from Earth observation to scientific research and even potential lunar or Martian missions.

The Context of Terrestrial AI Demand

The global artificial intelligence market has been experiencing explosive growth, with projections indicating continued expansion over the coming decades. This growth is fueled by breakthroughs in machine learning, deep learning, and natural language processing, leading to widespread adoption across industries such as healthcare, finance, automotive, and defense. However, the computational infrastructure required to develop, train, and deploy these AI models is colossal. Training a single advanced AI model can consume energy equivalent to that of several homes for a year, and the energy consumption of data centers worldwide is already a significant contributor to global electricity demand.

Terrestrial data centers face increasing pressure from energy costs, land availability, and environmental regulations. While significant strides have been made in improving the energy efficiency of these facilities, the sheer scale of future AI processing requirements suggests that novel solutions will be necessary. SpaceX’s orbital data center concept, while ambitious, attempts to address these systemic challenges by proposing a fundamentally different paradigm for AI infrastructure. The move to space could bypass some terrestrial constraints, although it introduces an entirely new set of engineering, logistical, and regulatory hurdles.

A Rapidly Evolving Orbital Landscape

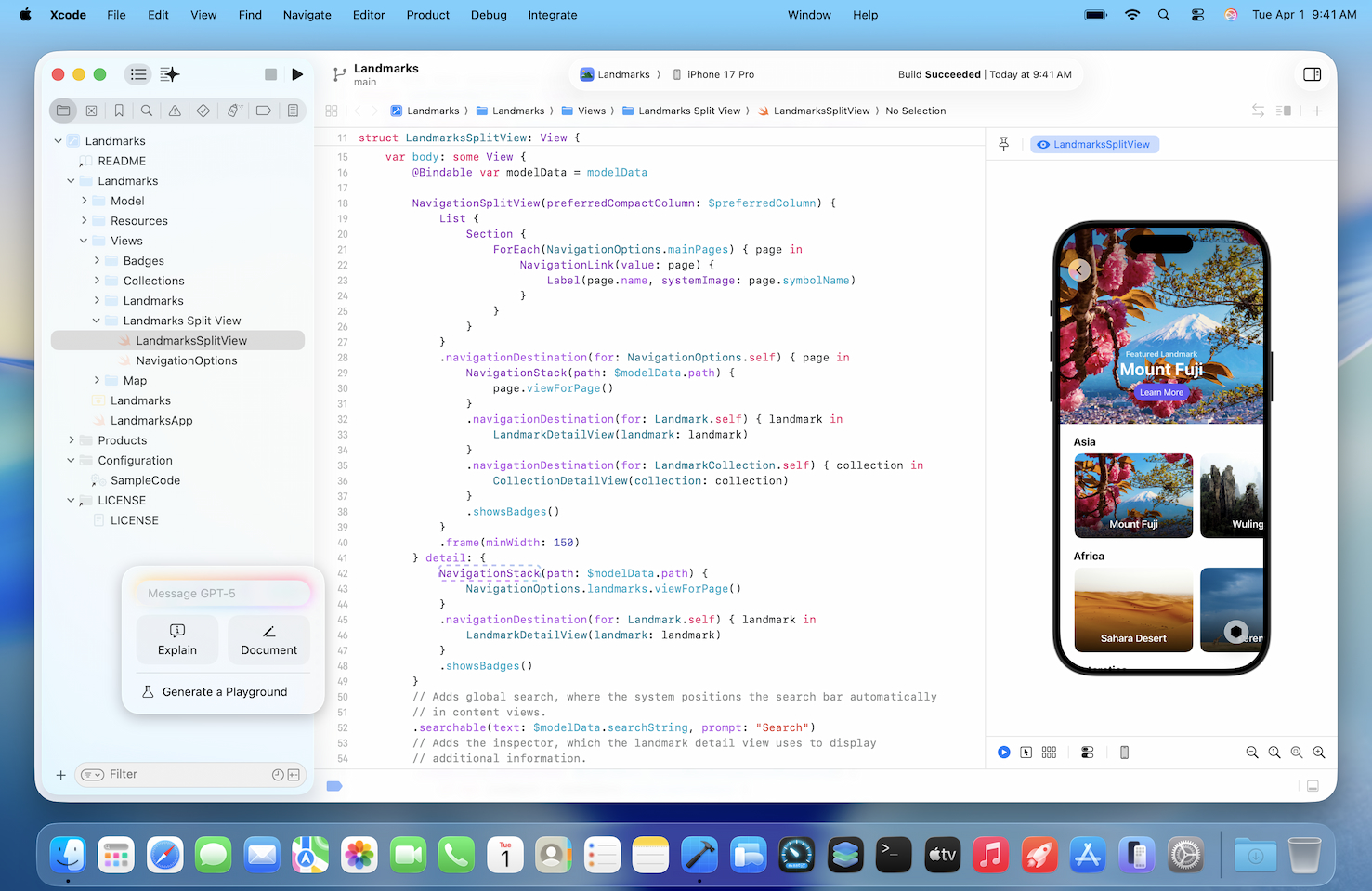

SpaceX is no stranger to large-scale satellite deployments. The company’s Starlink constellation, designed to provide global broadband internet access, already comprises several thousand operational satellites in low Earth orbit (LEO). This initiative has revolutionized satellite internet, demonstrating the feasibility and market potential of mega-constellations. However, the proposed one million AI data center satellites would dwarf Starlink and all other existing constellations combined by orders of magnitude.

Historically, the space environment was home to a relatively small number of large, expensive government and commercial satellites. The advent of smaller, cheaper CubeSats and the rise of private space companies like SpaceX ushered in an era of rapid deployment. The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that there are currently around 15,000 operational and non-operational man-made satellites orbiting Earth. The rapid increase in satellite launches, largely driven by Starlink, OneWeb, and Amazon’s forthcoming Project Kuiper, has already prompted significant discussions and concerns about orbital congestion, space debris, and light pollution.

The FCC, as the primary U.S. regulatory body for satellite communications, plays a pivotal role in licensing such operations. Its recent decision regarding Starlink’s expansion offers a glimpse into its cautious approach. While the FCC granted SpaceX permission to launch an additional 7,500 Starlink satellites, it explicitly deferred authorization on a further 14,988 proposed satellites, citing concerns about orbital debris and spectrum interference. This precedent suggests that the one million satellite proposal, though framed as a visionary long-term goal, is highly unlikely to receive outright approval in its current form and is more realistically a starting point for extensive negotiations and rigorous technical and environmental reviews.

Regulatory Scrutiny and Environmental Concerns

The prospect of one million new satellites raises a multitude of complex issues that regulators and the international space community must address. The most immediate and pressing concern is space debris. Even small fragments of defunct satellites or collision byproducts can travel at orbital velocities of thousands of miles per hour, posing a catastrophic risk to operational spacecraft, including human spaceflight missions like the International Space Station. The "Kessler Syndrome" describes a theoretical scenario where the density of objects in LEO becomes so high that collisions between objects create a cascade of further collisions, rendering certain orbital regimes unusable for generations.

Furthermore, a constellation of this scale would exacerbate light pollution, significantly impacting ground-based astronomy. Astronomers have already voiced strong concerns about the brightness and number of Starlink satellites interfering with observations, particularly for wide-field surveys. The proposed AI data centers, if similarly reflective, could fundamentally alter humanity’s view of the night sky and impede scientific research.

Spectrum allocation is another critical regulatory hurdle. Each satellite requires dedicated frequency bands for communication, and the sheer volume of proposed satellites would necessitate careful management to prevent interference with existing and future satellite systems, terrestrial networks, and scientific instruments. International coordination through bodies like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) would be essential, as orbital operations transcend national borders.

The Challenge of Scale and Sustainability

Beyond regulatory and environmental considerations, the practicalities of manufacturing, launching, and maintaining a million satellites present unparalleled engineering and logistical challenges. Each satellite would need to be designed for longevity and resilience in the harsh space environment, capable of self-correction or de-orbiting at the end of its operational life to mitigate debris. SpaceX’s Starship, currently under development, is envisioned as a fully reusable super-heavy launch system capable of deploying hundreds of satellites at once, which would be crucial for such a massive deployment. However, the successful and frequent operation of Starship at this scale is yet to be fully demonstrated.

The long-term sustainability of such a vast orbital infrastructure also comes into question. What happens when these satellites reach end-of-life? While active debris removal technologies are being explored, they are nascent and expensive. The sheer volume of material required for manufacturing, and the energy footprint of launches, even with reusable rockets, would be substantial. This highlights a tension between the goal of "green" space-based computing and the environmental impact of its creation and eventual disposal.

Competitive Dynamics and Broader Corporate Strategy

The timing of SpaceX’s filing also provides insight into the broader competitive landscape and the company’s internal strategic maneuvers. Amazon, a direct competitor in the satellite internet sector with its Project Kuiper, recently sought an extension from the FCC on its deadline to deploy over 1,600 satellites, reportedly citing a "lack of rockets" as a primary reason. This underscores the intense competition and the significant logistical challenges inherent in deploying large constellations. SpaceX’s ambitious proposal, made while a rival faces launch constraints, could be interpreted as a strategic move to stake out a dominant position in future space-based services.

Moreover, the news coincides with reports that SpaceX is considering a merger with two other companies controlled by Elon Musk: Tesla, the electric vehicle and clean energy company, and xAI, his artificial intelligence venture (which has already merged with X, formerly Twitter). This potential consolidation, reportedly preceding a highly anticipated initial public offering (IPO) for SpaceX, could create a formidable technology conglomerate spanning terrestrial and extraterrestrial domains. An orbital AI data center network would not only align with Musk’s vision of a multi-planetary future but also provide a powerful computational backbone for the AI ambitions of xAI and potentially integrate with Tesla’s growing need for advanced AI processing for autonomous driving and robotics.

Looking Ahead

SpaceX’s proposal to launch one million solar-powered satellite data centers represents a bold and visionary leap into the future of computing and space utilization. While the sheer scale of the project will undoubtedly face intense scrutiny from regulators, environmental groups, and the scientific community, it also signals a profound shift in how humanity might address its burgeoning computational needs. The path to realizing such a grand vision is fraught with unprecedented technical, economic, and ethical challenges, but it undeniably pushes the boundaries of what is considered possible, forcing a global conversation about humanity’s role and responsibility in shaping the future of space. The FCC’s eventual response will be a critical determinant in whether this ambitious dream takes its first concrete steps toward orbital reality.